The Panama Canal celebrates 100 years

1Monday 24 February 2014

2014 marks the centenary of the Panama Canal opening and Adina gets to transit it for the first time!

In preparation for our transit we’ve been doing a little bit of the good old studying of the history and workings of the canal, and for the curious amongst you we thought it would be good to share our findings.

It was the French under the leadership of Ferdinand de Lesseps, famed builder of the Suez Canal, who started work on the Panama Canal in 1881. Back then the Panama isthmus connecting North and South America was a hostile environment and proved very challenging for the pioneering engineers. With difficult geology and, more concerning, a high mortality rate as a result of malaria and yellow fever (it’s estimated a staggering 22,000 people lost their lives whilst working on the canal), financial problems and corruption, the French eventually went bankrupt.

Step in the Americans and, after a few political fallouts with Colombia who laid claim to the land, they went ahead with the Panamanians and started work in 1904. The Americans worked tirelessly to eradicate malaria and yellow fever and were credited with developing a skilled workforce to take on what was considered then to be the world’s most difficult engineering project. The key challenge for the engineers was carving a canal through a stretch of mountain ridge which today is called the Culebra Cut and runs for 8 miles (13km) in the southern stretch of the canal. Dynamite was used to blast through the rock and trains hauled the dirt out – dubbed by demanding Americans as ‘the need for dirt’. But the cut was plagued by landslides and had to be widened several times before the canal could be completed.

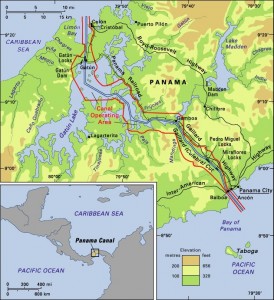

Ten years later the Panama Canal was officially opened. Its total length is 77.1km (48 miles) running from the Atlantic Ocean in the north to the Pacific Ocean in the south. Today it saves ships from having to travel around the Cape Horn of South America, a particularly hazardous route, and rightly stands proud as one of the seven industrial wonders of the World.

Locks each end of the canal are used to raise and lower vessels up to and down from the central Gatun Lake, an artificial lake formed by the building of the Gatun Dam, a challenging feat in itself.

On the Atlantic side, the Gatun locks, consisting of three linked locks 1.9km (1.2 miles) long in total, lift vessels to the Gatun Lake some 26.5m (87 ft) above sea level. Once into the Gatun Lake vessels travel 33km (20 miles) to the Culebra Cut which, as mentioned earlier, slices 12.6 km (7.8 miles) through a mountain ridge. The descent then begins with the Pedro Miguel lock which is 1.4km (0.87 miles) long and drops ships some 9.5m down. Following this, vessels move through the artificial Miraflores Lake, 1.7km (1.1 miles) long, to descend the final two linked Miraflores locks, 1.7km (1.1 miles) long and providing a total descent of 16.5m (54 ft). From the Miraflores locks one reaches Balboa harbour passing under the Bridge of the Americas and finally entering the Pacific Ocean.

On the Atlantic side, the Gatun locks, consisting of three linked locks 1.9km (1.2 miles) long in total, lift vessels to the Gatun Lake some 26.5m (87 ft) above sea level. Once into the Gatun Lake vessels travel 33km (20 miles) to the Culebra Cut which, as mentioned earlier, slices 12.6 km (7.8 miles) through a mountain ridge. The descent then begins with the Pedro Miguel lock which is 1.4km (0.87 miles) long and drops ships some 9.5m down. Following this, vessels move through the artificial Miraflores Lake, 1.7km (1.1 miles) long, to descend the final two linked Miraflores locks, 1.7km (1.1 miles) long and providing a total descent of 16.5m (54 ft). From the Miraflores locks one reaches Balboa harbour passing under the Bridge of the Americas and finally entering the Pacific Ocean.

Yachts are frequently transited in the evening through the floodlit canal. Transiting yachts on their own is considered too expensive due to the amount of water needed to flood the locks so locking with one of the large freighter ships is required. Each vessel is accompanied by a Panama Canal Advisor and has to have a skipper and four people to handle lines on the yacht.

While there are several methods by which yachts can be positioned for transit locks they are most usually rafted next to each other, up to three at a time, in a so-called nest. The raft is created before entering the locks. The centre yacht controls and steers the rafted nest first into the Gatun locks following the designated ship you lock in with. Lines with a monkey fist at the end are thrown to the yacht from shore and you attach these to your own lines which are then taken to the shore and the entire nest is secured within the lock by four lines (two each side, fore and aft).

While there are several methods by which yachts can be positioned for transit locks they are most usually rafted next to each other, up to three at a time, in a so-called nest. The raft is created before entering the locks. The centre yacht controls and steers the rafted nest first into the Gatun locks following the designated ship you lock in with. Lines with a monkey fist at the end are thrown to the yacht from shore and you attach these to your own lines which are then taken to the shore and the entire nest is secured within the lock by four lines (two each side, fore and aft).

The waters flood in fast and the line handlers on the yachts take in the slack as the vessel rises. On exit, the main danger is to watch out for the ship and tug boat ahead of you using any thrust to move forwards which can cause considerable turbulence. This process happens three times at the Gatun Locks.

The yachts then separate and proceed across the Gatun Lake, mooring overnight. The Gatun Lake, itself is a natural reserve with monkeys, alligators, jaguars and various wild birds in abundance. The Advisor departs only to be replaced by a new one early the next morning ready for the descent.

Vessels proceed through the Culebra Cut for 12.6 km (7.8 miles). The descent then begins with the Pedro Miguel lock, with a similar process to the ascent except this time the ship enters after the rafted yachts. Once through Pedro Miguel, the raft stays connected and moves through the artificial Miraflores Lake to descend the final two linked Miraflores locks. Watching out for a strong current caused by the outrushing fresh water mixing with seawater, the yachts separate for the final time and pass under the Bridge of the Americas reaching the Pacific Ocean.

Here Adina will stop a few days giving us a chance to see Panama City and celebrate being in the Pacific Ocean. After that we head to the Las Perlas islands to prepare to cross to the Galapagos Islands.

We are scheduled to be at the small vessel anchorage near the Gatun Locks at 5pm local time (10pm UK, 11pm SA, Aus 8am) to await our advisor coming on board. We have some Swiss sailors joining us to help as line handlers prior to doing their own transit.

To say it’s a trip we’re excited about would be an understatement, a little nervous yes, you need to have your wits about you, your yacht endures stresses it’s never had to as it goes up and down mammoth locks designed for large ships. But most of all we want to take in the history of the Panama Canal, enjoy it, and appreciate this marvellous engineering feat.

And perhaps a little celebration on the other side when we reach the Pacific Ocean.

A number of things immediately stand out as incredible when considering the gargantuan engineering feat that created this passage, so long ago. Firstly, that surveyors could penetrate the jungles at that time and come up with a workable design. No satnav or geodessy then!

Secondly that one hundred years ago, when the mode of powered sea transport was sail/steam driven, the designers/engineers had the foresight to realise that by 2014 (and maybe greater beyond?) shipping dimensions would increase incredibly to those of todays tankers and cargo vessels.

And lastly (or perhaps firstly) that the deaths of some 22,000 individuals, through disease and/or injury was the right price to pay to achieve the end result of an alternative to the NorthWest passage or the cape.

Bon voyage, and continue to keep safe and well.

Mal Keenor